Take home message

- There are basically two essential plant-based polyunsaturated fatty acids in our diet: linoleic acid (LA n-6) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA n-3). For health purpose, it is important to look after the ratio between these two fatty acids, in favour of a low LA n-6 and a high ALA n-3.

- In young animals, these essential fatty acids are reprocessed into very long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, also known as the fish fatty acids. The ratio in the diet (LA / ALA) is reflected in the liver, but not in the brain. Apparently, the brain filters out the right fatty acids from the blood to build the brain.

- Behaviour of young animals showed that ‘fear’ and ‘exploration’ are partly affected by ALA n-3 or LA n-6 in the diet. ALA n-3 reduces ‘anxiety’ and increases ‘exploratory behaviour’ and ‘rooting behaviour’, which is interpreted as a positive outcome, unlike LA n-6.

- Cow’s milk also provides essential fatty acids. To get enough ALA n-3 from dairy fat, it is important that animals produce milk from grass, hay or grass silage and not from maize silage and concentrates.

Plant-based, essential unsaturated fatty acids

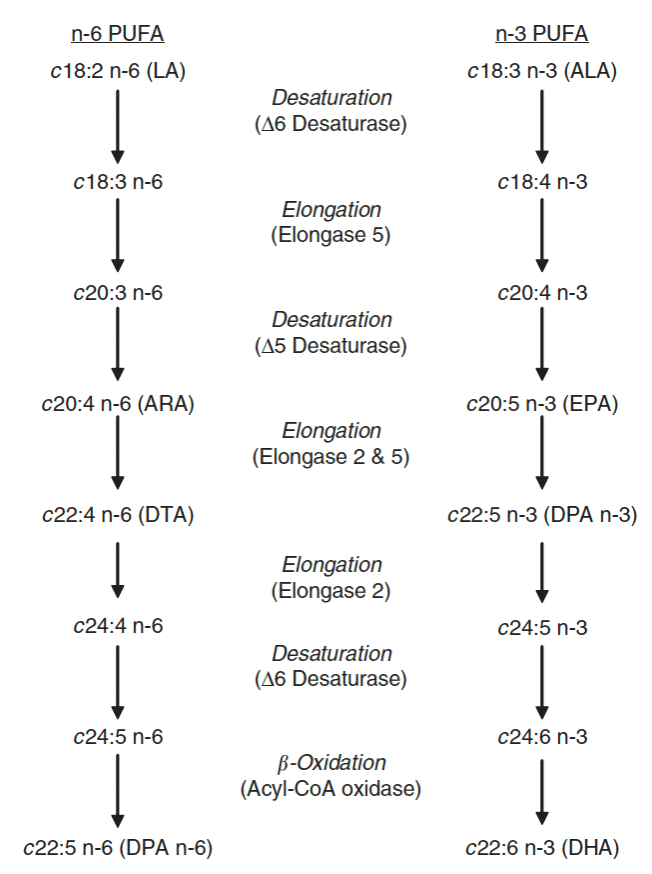

The plant produces some essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (Eng.: PUFA), namely linoleic acid, C18:2 n-6 (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid, C18:3 n-3 (ALA). As humans, we ingest these fatty acids through diet. Both fatty acids have a carbon skeleton of 18 C atoms, C18:2 with two, C18:3 with three double bonds. In steps, these fatty acids are ‘reprocessed’ in an animal’s body into very long-chain fatty acids, the fish fatty acids, which get their name from consuming high-fat fish from cold marine waters (Fig. 1). Two types of enzymes are involved in reprocessing, by: (1) chain lengthening by 2 C-atoms each, and (2) splitting off 2 hydrogen atoms, adding an extra double or unsaturated compound. Curiously, there is competition between the n-3 and n-6 fatty acids, both of which use the same route and enzymes.

The reprocessing of fatty acids produces several fatty acids, which are important for the brain. Brain tissue is fat and contains high concentrations of Arachidonic acid (= ARA; C20:4 n-6) and Docosohexaenoic acid (DHA; C22:6 n-3). At the stage of brain development as a foetus and as a nursing baby, many of these very long-chain fatty acids are needed, both n-3 and n-6.

Fatty acids in Western diets

One of the problems of the Western diet is the excess of n-6 fatty acids, and therefore an excessive ratio of n-6 to n-3. Wageningen researchers investigated the effects of the two plant-based essential fatty acids (ALA n-3 and LA n-6) in young piglets (Smink et al., 2012). As experimental animals, piglets are a better reflection of humans than mice. Humans and pigs are very similar in terms of metabolism and organs. It was assessed how the fatty acid composition in the diet affected blood and brain concentrations, but also how the piglets’ behaviour was affected.

After weaning at 7 weeks of age, four feeding groups were built (combinations of low and high LA or ALA) by giving different combinations of oil from sunflower, linseed and palm oil in addition to piglet feed. The fatty acid intake for 4 weeks is shown in table 1 and importantly, each diet was otherwise free of other very long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, the so-called fish fatty acids (EPA, DPA, DHA and ARA). Therefore, it was possible to measure the conversion activity and the competition between essential n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in the diet. To keep the number mess somewhat clear, in Tabel 1 only the groups whose, either LA was elevated or ALA, and compared to a diet with both low LA and ALA as controls are presented. The elevation of both fatty acids has been omitted from the tables, without compromising the understanding of the outcomes.

Table 1. Intake of two essential fatty acids in g/kg body weight0.75. The group with low LA plus low ALA (1) was taken as a control for the other groups (= 100) and the real intake (in g/day) is shown in brackets. The experimental groups are shown in relative terms only.

| Control (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| LA in diet | Low LA | Low LA | High LA |

| ALA in diet | Low ALA | High ALA | Low ALA |

| Intake: | |||

| C18:2 n-6 LA | 100 (1.32) | 100 | 200 |

| C18:3 n-3 ALA | 100 (0.15) | 993 | 107 |

The intake of C18:2 n-6 LA in the High LA group (3) was increased by a factor of 2 compared to the control (1); however, the intake of C18:3 n-3 ALA in the High ALA group (2) was increased by a factor of almost 10. The group (3) with a low intake of ALA and a high of LA reflects a modern Western diet.

Fatty acids in liver and brain

One determined both the liver (Table 2) and the brain (Table 3) concentration of the essential fatty acids, as well as the very long-chain fish fatty acids, generated by the metabolism of the piglet.

Table 2. Some n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in the liver of young, growing piglets with different dietary ratios between ALA and LA. The group with low LA, low ALA (1) was taken as control for the other groups (= 100) in each case and the concentration is shown in brackets. The other two groups are shown relatively only.

| Control (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| LA in diet | Low LA | Low LA | High LA |

| ALA in diet | Low ALA | High ALA | Low ALA |

| n-6 fatty acid: | |||

| C18:2 n-6 LA | 100 (16.4) | 102 | 129 |

| C20:4 n-6 ARA | 100 (17.4) | 51 | 111 |

| n-3 fatty acid: | |||

| C18:3 n-3 ALA | 100 (0.5) | 1060 | 92 |

| C20:5 n-3 EPA | 100 (0.6) | 1402 | 48 |

| C22:6 n-3 DHA | 100 (2.6) | 89 | 80 |

The level of two fatty acids LA and ALA in the diet (Table 1) mirror the values in the liver (Table 2). Looking at the reprocessing to the longer chain fish fatty acids, the comparison of group (2) and (3) showed, that the reprocessing to DHA n-6 is reduced by the high concentration of ALA (group 2), and conversely, the reprocessing to EPA n-3 and DHA n-3 is complicated by the high concentration of LA (group 3). Group 2 also showed that the last step in the elongation, from EPA to DHA did not or hardly took place, despite the high ALA n-3 supply; rather, there seems to be an inhibition in the conversion step. The largest concentration increase was due to elongation to EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) from ALA n-3.

The question was, how the ratio LA n-6 / ALA n-3 in the diet ultimately determined the fatty acid composition in the brain (Table 3)? The measurements took place in the frontal cortex, the largest part of the brain, where most primary functions are regulated.

Table 3. ESome fatty acids in the brain of young, growing piglets with different dietary ratios between ALA and LA. The group with low LA plus low ALA (1) was taken as control for the other groups (= 100) in each case and the absolute concentration is shown in brackets. The other two groups are shown relatively only.

| Control (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| LA in diet | Low LA | Low LA | High LA |

| ALA in diet | Low ALA | High ALA | Low ALA |

| n-6 fatty acid: | |||

| C18:2 n-6 LA | 100 (0.7) | 116 | 114 |

| C20:4 n-6 ARA | 100 (8.9) | 95 | 101 |

| n-3 fatty acid: | |||

| C18:3 n-3 ALA | 100 (0.6) | 110 | 116 |

| C22:5 n-3 DPA | 100 (0.2) | 233 | 88 |

| C22:6 n-3 DHA | 100 (7.8) | 105 | 88 |

The fatty acid composition in the brain is no longer a truly reflection of the dietary fatty acid supply. There is hardly any suppression of ARA n-6 when richly fed ALA n-3 (group 2) and conversely when fed DPA or DHA n-3 (group 3). Rather, the brain regulated its own need for n-6 and n-3, despite differences in feed supply and the stored fatty acids in the liver. The autonomy of the brain has to do with the importance of its functioning to the organism. Visible is, however, that in group (2) there is enrichment of C22:5 n-3 DPA (Docosapentaenoic acid), a fatty acid, which stands between EPA and DHA (Fig. 1).

Summarised, it is striking, that the ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acid depended mainly from the tissue (diet, liver or brain), not the diet (Table 4).

Table 4. Ratio of n-6 / n-3 fatty acids. Above the LA / ALA ratio in diet, liver and brain; below the ARA / DHA ratio in liver and brain.

| Control (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| LA in diet | Low LA | Low LA | High LA |

| ALA in diet | Low ALA | High ALA | Low ALA |

| LA / ALA in: | |||

| Diet | 8.8 | 0.9 | 16.5 |

| Liver | 34.2 | 3.3 | 48.2 |

| Brain | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| ARA / DHA in: | |||

| Liver | 6.6 | 3.8 | 9.2 |

| Brain | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

The dietary LA to ALA ratio was further magnified in the liver. On the brain, on the other hand, this ratio had no impact. Looking at the elongated n-6 and n-3 fish fatty acids (ARA / DHA ratio), this ratio in the liver still corresponds to the supply in the essential dietary fatty acids; however, in the brain these values creep closer together again. Attenuated, it was still recognisable that a high LA / ALA supply led to higher ARA / DHA ratios and vice versa.

Piglet behaviour

In another article, Clouard et al. (2015) showed the impact of differences in essential fatty acids on the piglets’ exploration behaviour and anxiety. The animals were housed individually, and no social behaviour was possible (Table 5). On days 12 and 18 of their diet, the piglets were examined for exploratory behaviour and rooting behaviour. Furthermore, it was assessed, how long the animals were resting with opened eyes, as a measure of anxiety. Shown is the proportion of total time, which the animals spent on each type of behaviour (Table 5).

Table5. Significant different behaviour in piglets. The group with low LA, low ALA was taken as control (1) for the other groups in each case (= 100) and the proportion of total observation time is shown in brackets. The other two groups are only shown relatively.

| Control (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| LA in diet | Low LA | Low LA | High LA |

| ALA in diet | Low ALA | High ALA | Low ALA |

| Behaviour: | |||

| Resting with opened eyes | 100 (22.5%) | 73 | 99 |

| Exploring | 100 (12.8%) | 115 | 78 |

| Rooting | 100 (9.2%) | 125 | 82 |

If an animal lied down or was resting with its eyes closed, this is an indication that the animal is at ease. If the time, when an animal lied with its eyes open, increased, this was interpreted as the animal being ‘less at ease’. Positive behavioural elements were exploratory behaviour and rooting behaviour. Exploration meant, that the animal dispersed with its environment and rooting was simply a basic behaviour of a pig. The group (2) with an increased proportion of n-3 ALA fatty acids in their diet distinguished itself positively: animals showed more confidence towards the environment and more species-typical behaviour. The opposite was found in the animals with an increased n-6 LA diet (group 3).

In addition, other behavioural elements were scored, and results pointed in the same direction. Furthermore, correlations were calculated between the concentration of AA n-6 and DHA n-3 in the brain of individual piglets and the extent of the above-mentioned behaviours. It could be deduced from this, that the higher the concentration of AA n-6, the more time the animals spended resting with opened eyes. In other words, the more AA n-6, the more ‘anxious’. Between the DHA n-3 in the brain and the time used for exploration, the relationship was positive. In other words, the more DHA n-3, the more ‘curious’. The researchers indicated, incidentally, that other studies also found such correlation between the n-6 and n-3 ratio in the diet or blood and behaviour.

In summary, the ratio of essential, polyunsaturated fatty acids in the diet, ALA n-3 and LA n-6, did not much change the accumulation of very long-chain fatty acids in the brain, but did change behaviour. Exploratory behaviour and behaviour indicating confidence in the environment (non-anxiousness) were correlated with the very long-chain fatty acids DHA n-3 (positive) and ARA n-6 (negative).

Lack of oily fish from wild catch

The dietary advice is to eat oily fish on a regular basis to have a high enough intake of the very long-chain n-3 fish fatty acids (DHA and EPA). Environmental pollution and the depletion of seas and oceans are forcing us to look for alternatives. Given the current overconsumption of n-6 fatty acids by meat (chicken, pork) and fats based on palm oil and soybean oil, consumption of pasture-raised milk, as well as walnuts, and linseeds comes into focus as vegetarian alternatives.

Farmers, who lived in the Swiss Lötschen valley lived off the milk, butter and cheese of cows that grazed the summer pastures (WA Price, 1933). We now know that such summer milk fat has an n-6 / n-3 ratio of about 1.0. Milk fat consists largely of the essential fatty acids ALA n-3 and LA n-6, however in a favourable ratio compared to dairy cattle, which produce milk from maize silage and concentrates. A 2nd alternative comes from one of the so-called blue zones, the areas of the world, where proportionally many 100-year-olds live. This is the group of vegetarian Seventh Day Adventists. Analyses of their diet have revealed that these people eat a high proportion of ALA n-3 rich walnuts.

Mountain dairy farmers and vegetarian Seventh Days Adventists are two examples, how you can steer through food choices the ratio LA n-6 / ALA n-3 in favour of the n-3 fatty acids, without dependence on oily fish. Swiss farmers never had access to such fish; Seventh-day Adventists were vegetarian anyway. Yet both groups of people lived happily ever after, even without fish.

Literature

Smink, W., Gerrits, W. J. J., Gloaguen, M., Ruiter, A., & Van Baal, J. (2012). Linoleic and α-linolenic acid as precursor and inhibitor for the synthesis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in liver and brain of growing pigs. Animal, 6(2), 262-270.

Clouard, C., Gerrits, W. J., van Kerkhof, I., Smink, W., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2015). Dietary linoleic and α-linolenic acids affect anxiety-related responses and exploratory activity in growing pigs. The Journal of nutrition, 145(2), 358-364.