Take home message

- There are two ways to soften butter, through technology (cream preparation process) and through the cow’s diet (ratio of unsaturated to saturated fat).

- Softening butter makes it more spreadable, especially at lower ambient or storage temperatures in winter, when cows do not have access to fresh grass.

Realising spreadable butter kept at low ambient temperature

Butter competes with margarine and ‘spreads’ when it comes to spreadability. Butter is a natural product with different fatty acid composition in summer or winter. Margarine is made up of plant oils with a low melting point and is always the same spreadable product, even when stored in the fridge. But how do you make soft butter, especially at lower storage temperatures? The dairy industry had to find an answer to this. Butter is created by churning cream; the fat globules transform into grains of butter. Kneading and washing the butter grains squeezes out the moisture and creates an even product: butter. Butter is an emulsion, which is small amounts of water kneaded into an oil substance. Butter can legally contain no more than 16% moisture, and this water can be trapped in the fat in various ways. Besides the fatty acid composition (saturated, mono-, poly-unsaturated), the structure of the emulsion determines the spreadability of butter. Butter makers can influence this by playing with the ripening temperature of their cream.

Naturally soft butter through grass

The Dutch broadcast of “Keuringsdienst van Waarde” (9 Sept 2021) looked at difference in firmness of butter. There are differences between butter origins and the focus was on the impact of palm fat, but also the season (summer, winter) and the cows’ diet. Whereas dairy cows in the 1950s were fed grass and grass products, supplemented with cakes based on linseed and cereals, in 2025, cows are bigger, produce more milk, often remained indoors year-round and fed maize silage, grass silage, and a high amount of concentrates (based on soy, cereals, waste products), supplemented in the last decade by palm fat. Large skinny Holstein cows (HF) should produce a lot of milk per day. The cubicle barn (developed in the 1960s and 70s) and the cultivation of maize (since the 1970s and 80s) have greatly changed dairy farming along with HF breeding. High intake of starch (maize, concentrate feed) affected the firmness of butter. Later, palm fat added into concentrates further increased this. In contrast, with a diet of fresh grass, cows can naturally offer soft butterfat. Background is the change in fatty acid composition, more unsaturated fat is secreted into the milk.

Technically soft due to ripening of the cream

There is another way to get soft butter, which is through the ripening process of the cream. This is a somewhat time-consuming process, and the industry does not always take the time for this. Traditionally, the dairy plant had two problems: too hard winter butter (impossible to dent in a packet of butter) and too soft summer butter (the butter runs off your knife), caused by feeding hay plus fodder beet (winter) and lots of fresh grass (summer) respectively. There was winter or butter plus stable cheese versus grass cheese plus grass butter. When the season changed, the dairy plant shifted from a full yellow to even orange colour (summer beta-carotene) to a white colour and pale barn cheese when the cows were fed inside in November.

Butter is often stored in the fridge at temperature below 8 oC. The butter makers’ task was to make a spreadable product in the temperature range from fridge to room temperature (8-20 oC). They discovered, that by manipulating the ripening temperature of the cream before churning, the firmness of butter changed. To do this, pasteurised cream was first cold ripened in winter, then warm ripened and finally churned cold (11 oC). The crystal structure of the butter changed, and the butter became more spreadable, softer. This means, you can still get softer butter with a low percentage of unsaturated winter fat.

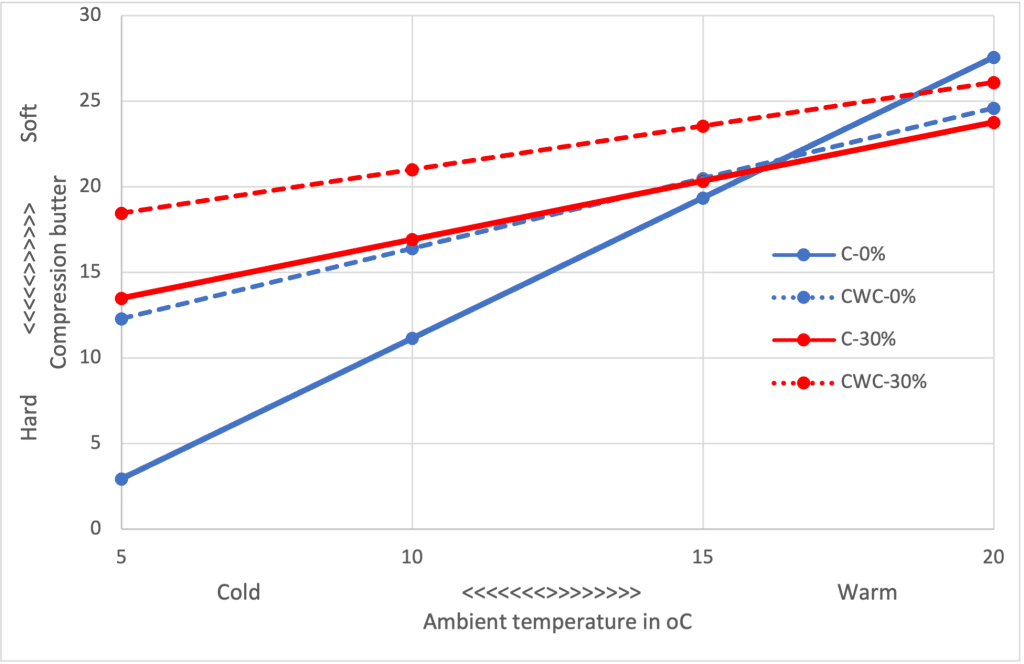

In the literature, there are several publications on the topic of cream ripening. Schäffer et al (2001) showed, how both factors (feeding the cow and ripening of cream) affect the final product in terms of spreadability. The researchers used winter butter. At first, they added a certain amount of unsaturated fatty acids to the cream. Figure 1 shows the differences with 0 and 30% addition, respectively (the blue and red lines). Butter was then made from the two cream types in two ways: the quick way (without ripening steps) and by ripening the cream in the cold-hot-cold sequence (6o C, 20o C and 11o C). In Figure 1, this is denoted by C or CWC, respectively, visible as solid or dashed lines. Using a measuring instrument, the penetration resistance of the butter was objectively measured at different storage temperatures (5, 10, 15 and 20o C).

Comparing the lines in Figure 1, you can see that at low ambient temperature (refrigerator temperature 5 oC), there is a big difference between the four butter types. Normal butter made from winter cream is firm, hard (C-0%). If you make butter from either more unsaturated fat (grass-fed butter) (C-30%), or if you change the ripening process of cream (cold-warm-cold), (CWC-0%), the butter becomes a lot softer and more spreadable. When you combine both aspects, the softest butter will be made, if kept at 5 oC (CWC-30%). From left to right in the graph, all four types of butter become softer with increasing room temperatures. Somewhere at about 16 oC, the differences between the four butter types disappear and above this ambient temperature, all butters are similar in spreadability.

Literature

- Schäffer, B., Szakály, S., & Lőrinczy, D. (2001). Melting properties of butter fat and the consistency of butter. Effect of modification of cream ripening and fatty acid composition. Journal of thermal analysis and calorimetry, 64(2), 659-669.

Foto: orange-yellow butter made in summer at Alp Zillis (CH).