Growing interest for the gut and its microbiome

What is a healthy gut? What microbiome belongs to it? How do you steer health, and especially from what age? This kind of research is much needed, because the list of diseases of affluence is growing rapidly. Think of obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, but also the range of intestinal problems (irritable bowel, Crohn’s disease), or colon cancer. There is increasing evidence, that there is a causal relationship between the gut composition and, for example, our skin health, or our brain functioning, the so-called ‘gut-brain-axis’. Examples of brain-related diseases are Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, but also autism and depression. Not unimportant is also the mother-baby-axis (Miko et al., 2022). With pregnancy, birth and in the so-called 1st 1,000 days of life, the basics are developed for our gut flora composition, our metabolic health and the way we will grow old. Important to stay healthy, is the carefull use of antibiotics and the composition of the diet.

We must learn to love our gut. Between me/myself and my gut flora, a true symbiotic relationship is present. If I feed my gut and its micro-life well, my gut flora in turn feeds me (with vitamins, metabolites, etc) and thereby keeps me healthy (Dinan et al., 2022; Ghosh et al., 2022).

The microbiome unravelled

Through DNA and RNA research, you can now call any microbe by name. Meanwhile, through metagenomics research you can also understand the relationship between composition and functioning. An important part of the gut bacteria contributes to the digestion of food, but another part is there to keep the gut functioning. This means, maintaining the mucus layer (mucus), building the villi and crypts, keeping the gut closed to too large molecules (leaky gut). These are examples of gut functions as a prerequisite for digestion, poop consistency, health and disease.

Another way of looking at the composition of the gut flora is through the classification ‘Pathobionts’ versus ‘Commensales’, or pathogens and blackheads. Several bacteria from the genus Clostridium, Streptococcus are increasing, as people get sick, or older. Other genera like Alistipes, Coprococcus and Bifidobacterium belong to the commensals; that decrease during illness. This insight was deduced after comparing the gut microbiome of more than 3,000 people from all parts of the world, ages and different lifestyles (Shanahan et al., 2021). Aging, Western lifestyle and diet, repeated use of antibiotics harm the gut flora resulting into a dysbiosis, which means impoverishment of biodiversity and an increase of pathogens. We all die once, but the question is, how to slow down the timing of degeneration, inflammation, gut dysbiosis, alzheimer, and diseases of affluence. There is a difference between growing old and growing old healthily (Ghosh et al., 2022). Typical of ageing, there is a decline in gut functions, decreased immunity and a build-up of chronic inflammation (low grade inflammation).

The ageing microbiome

A well-known group of elderly people is the Centenarians, the over 100-year-olds in various hotspots around the world. People who remain healthy, still have a social life, and are physically active. One such group is on the Italian island of Sardinia. A recent study compared the microbiome of the over-100-year-olds, the 90-100-year-olds with a control group, namely their children (Palmas et al., 2022). The mean age of the three groups was 102, 93 and 62 years, respectively, and in each group around 80% women. Striking microbiome changes are found among the healthy Centenarians: there is (1) a decrease in the number of different taxa, meaning the diversity of species, genera, families decreases; (2) a shift in the ratio between the two main groups Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. This F/B ratio increases in older people. A biomarker in the gut of Centenarians is the bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila. It is the bacteria found in association with a healthy gut (called ‘gut homeostasis’ and supporting ‘the intestinal integrity’). There were 13 groups of bacteria correlated with both the Mediterranean diet and the number of times of toilet visits/week (= bowel function). Declining toilet visitation is a problem in the elderly.

Besides the loss of the ‘core microbiome’ in ageing people, there is an increase of unwanted disease-associated bacteria, such as various species of Clostridia. Yet Ghosh et al (2022) conclude, that ‘the fragile balance and limited physiological reserve of some elderly people may already mean that relatively small improvements in the microbiome can have a profound impact on the individual’s functioning.’ This offers hope, and the question is in what could be done to improve and maintain the gut functioning in elderly people the elderly person in terms of gut function? Thereto the researchers hypothesise, if: ‘the intestinal ecosystem of older people can be ‘re-wilded’ by bringing back missing or lost strains of bacteria? What is the optimal way to restore the microbiome? What are the nutritional requirements for maintaining a restored microbiota?’

Fermented products like kefir

Eating fermented products affects the composition of the gut microbiome in the short and long term and should be an important part of our diet (Leeuwendaal et al., 2022). Kefir is one such fermentation product from milk. Kefir consumption offers opportunities in supporting the gut to stay healthy. Among fermented products, ‘kefir is gaining popularity, largely due to an increased appreciation of its potential health benefits. Benefits of specific kefirs (read: containing certain bacteria and yeasts) include anti-cancer, immunomodulatory, cholesterol-lowering and other metabolic health improvements.’ (Bourrie et al, (2022). These benefits refer to a range of conditions that come with ageing and especially being sick in old age. In their own research, Bourrie et al (2022) describe effects of certain types of bacteria and yeasts, which they selected from traditional kefir grains for a new type of starter culture. Their focus is on the postbiotic properties of kefir, namely the range of bioactive compounds made by the fungi and bacteria after ingestion of kefir. However, the research shows, that both the intake of live bacteria and yeasts (probiotics) together with the metabolic products of the kefir microorganisms (postbiotics) are responsible for the improved health of laboratory animals that, like modern Western humans, live on a diet high in hidden fat (high-fat diets).

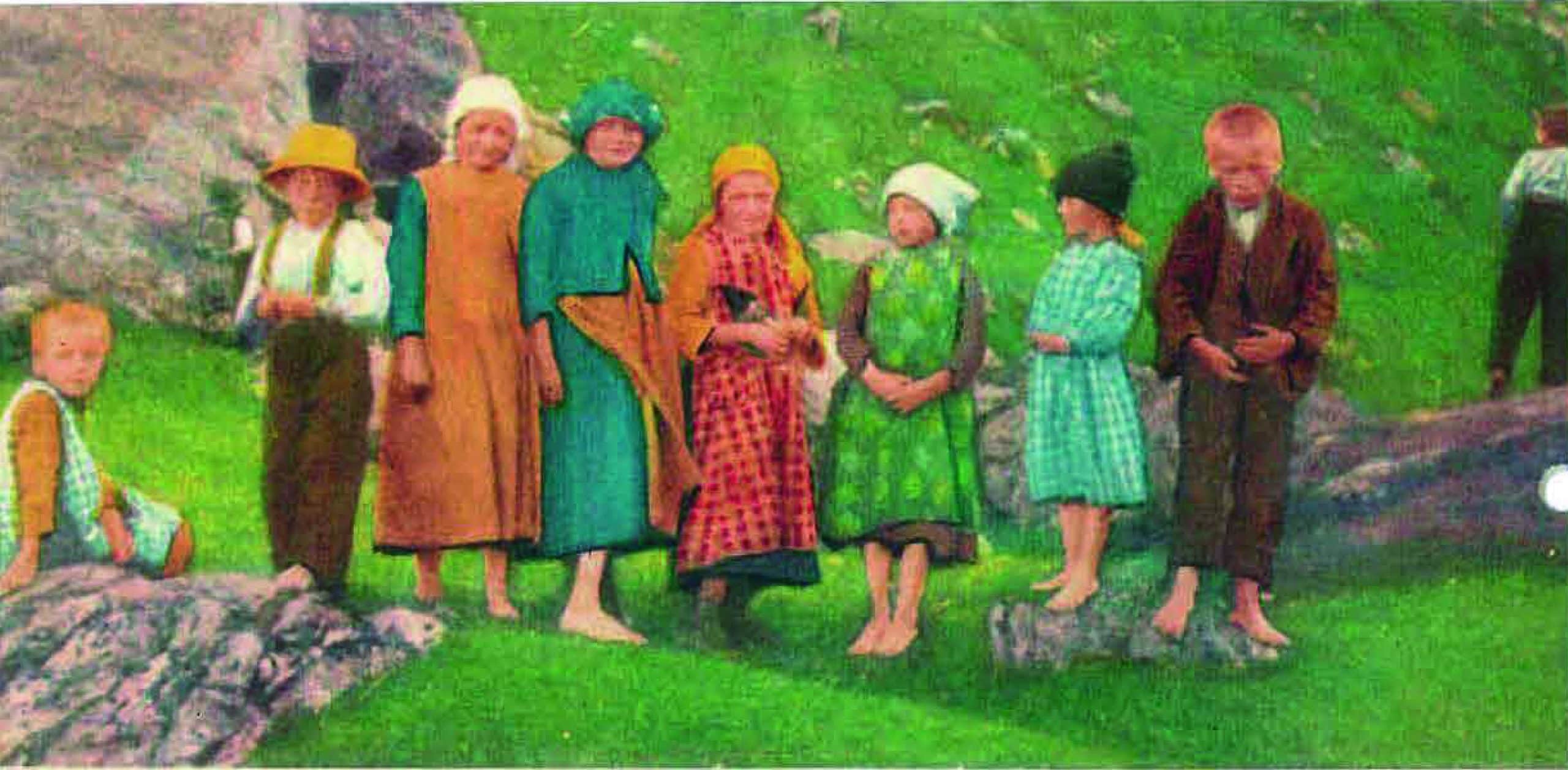

Traditional lifestyles

There are several imaginative studies, such as the effect of poop transplants (inserting poop from a healthy person into the intestine of a sick person). Also, the migration studies of people from Greenland to Denmark or people of India to England. What happens to them, why do they get as sick as the people they ended up among and, conversely, what changes when they switch back to the traditional diet from the area they came from in their new habitat? Intriguing studies, showing, how the functioning of the gut can both lead to disease and health. They are all indications, that traditional diets and traditional lifestyles are an important contribution, how to live healthier for longer.

Literatuur

- Bourrie, B.C.T., Forgie, A.J., Ju, T., Richard C., Cotter, P.D. & Willing, B.P. (2022) Consumption of the cell-free or heattreated fractions of a pitched kefir confers some but not all positive impacts of the corresponding whole kefir. Front. Microbiol. 13:1056526.

- Dinan, K., & Dinan, T. G. (2022). Gut Microbes and Neuropathology: Is There a Causal Nexus? Pathogens, 11(7), 796.

- Ghosh, T. S., Shanahan, F., & O’Toole, P. W. (2022). The gut microbiome as a modulator of healthy ageing. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 1-20.

- Leeuwendaal, N. K., Stanton, C., O’Toole, P. W., & Beresford, T. P. (2022). Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients, 14(7), 1527.

- Miko, E., Csaszar, A., Bodis, J., & Kovacs, K. (2022). The Maternal–Fetal Gut Microbiota Axis: Physiological Changes, Dietary Influence, and Modulation Possibilities. Life, 12(3), 424.

- Shanahan, F., Ghosh, T. S., & O’Toole, P. W. (2021). The healthy microbiome—what is the definition of a healthy gut microbiome? Gastroenterology, 160(2), 483-494.

Foto: children in the Swiss Lötschen valley (around 1930)