Kefir, including the raw-milk variety, is on the rise. There is a revaluation of fermentation, as a measure to ‘work up’ foods: white cabbage becomes sauerkraut, black tea with sugar Kombucha and milk becomes kefir. Meanwhile, raw milk kefir from the Raw Milk Company (The Netherlands) is available in every corner of the Netherlands and Flanders. The reason people choose kefir is mainly because of health problems that can be reduced through regular (daily) consumption. The quality of life improves.

Kefir is a relatively unknown product and for acidifying milk, it is rather yoghurt, cottage cheese or buttermilk that define the market, all acidified milk varieties without yeasts and moulds. Kefir, unlike yoghurt or buttermilk, has something pungent; there is carbonation by the yeasts, which is lacking in yoghurt.

Kefir late 19e century

Kefir was written in different ways: Kephyr, Kefyr or Kaphyr and was known as a frothy, fermented milk drink, originating from the Caucasus mountains. Other sources rather mention the nomads who grazed the Caucasian steppes with their herds (cows, yak, horses). Eckervogt wrote in 1890: “On Mount Elbrus and Kazbek in the Caucasus Mountains, it has been the custom of the people since time immemorial to prepare a light alcoholic drink from cow’s milk by throwing in a cauliflower-like plant”. The root of kefir = ‘Keph’, which means as much as ‘Wonnetrunk’ in German, in English: drink of bliss. The name ‘Keph’ is said to come from the Russian Tatars, and from Crimea to China, these nomads lived on the steppes. Others call kefir (from horse milk) a ‘sparkling milk wine’. Kefir is often mentioned in the same breath as Kumys, made from horse’s milk. Kefir is made with the milk of ruminants (cow, sheep, goat). Horse milk has more than 6.5% lactose compared to cow milk around 4.5%. After fermentation, more lactic acid can be formed in mare’s milk (Kumys) and is therefore more acidic in taste than after acidification of cow’s milk (Kefir). Both products rely on fermentation by bacteria plus fungi/yeasts.

Kefir in spas

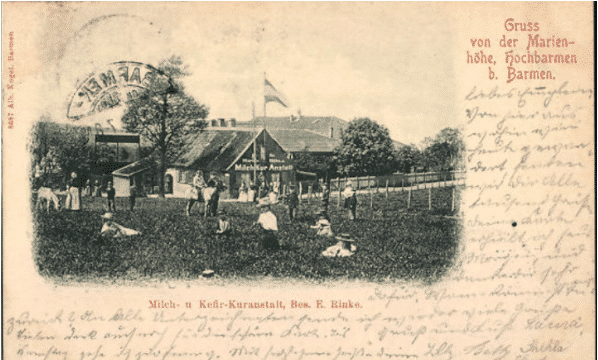

Kefir was brought to Europe by Russian migrants (refugees) as early as the late 19th century. The Jewish Russian Axelrod supplied kefir to the Züricher Kantonspital (Figure 2). He had brought the knowledge with him from his homeland and was able to prepare different strengths of kefir with good precision (see below), each with its target group of patients. Both Switzerland and Germany first reported several ‘kefir spas’ in the late 19th century and early 20th century, in Germany in 1882 (Figure 1). Russia had kefir spas earlier, and also used kefir in recovery of soldiers in army hospitals. A cure started with about 1/2 litre of kefir a day and could increase to 3-4 litres/day. A cure could quietly last 3 months.

In terms of effect, the kefir spas differentiated between the degree of fermentation. One-day mild kefir (Dschuurt) was said to have a purifying effect, problems with bowel movements (constipation) were solved with three-day fermented kefir (Airan). Furthermore, even then kefir was used to help people get rid of anaemia; it stimulated the desire to eat and people regained colour. Interestingly, kefir is also mentioned in the context of recovery from TB (pulmonary tuberculosis). Just as Europeans were sent to the Swiss mountains when there was asthma or recovery from TB, Russians went to the Caucasus. Whether it was the mountain air or the kefir, which had a healing effect, is not known. It is known, however, that TB did not occur among the Swiss mountain farmers and not among the peasants of the Caucasus. Both groups lived higher up in the mountains. Even earlier (in the 16e century) there is talk of whey (from cheese, quark or hangover) being used against TB.

Fig. 1. Milk- and kefir-spa in Hochbarmen (D) (ca 1890)

Fig. 2. Swiss kefir in the early 20th century.

What works?

Anno 2024 we understand better and better, how kefir works. Certain bacteria in kefir are probiotically active. This also applies to various fungi and yeasts. Kefir contains a very high number of lactic acid-forming bacteria, some of which reach the gut alive. Together, the micro-organisms produce a whole line of bioactive peptides, as they cut up the milk protein and especially the beta-casein into small pieces. The actions of these larger and smaller peptides have been linked to blood pressure regulation/lowering, controlling blood sugar, bone formation, or immune functions. In some studies, there is a difference between kefir from raw milk or heated milk. As in the research on milk, it became clear, that the whey fraction in the raw milk is important for the immune-supporting properties of the raw milk. Does the same apply to raw milk kefir?

Clinically, it is noticeable, that patients using kefir get healthier skin, free of scabs or eczema, that their daily bowel movements become easier, more regular and of better consistency. Old (late 19e century) and new experiences (early 21e century) in terms of health effects of kefir partly overlap, and partly are now confirmed in recent human and animal research.

Photo: Before (top) and after (bottom) regular consumption with raw milk kefir

Literature

- Düggeli, M. (1938). Die Mikroflora der Sauermilcharten und deren Verwendung. Pathobiology, 1(1-6), 273-312.

- Eckervogt, R. (1890). Kefir, seine Darstellung aus Kuhmilch. Heuser’s Verlag, Berlin. 21 pp.

- Spiekerman U. (2018). Der Revolutionär als Unternehmer – Pavel Axelrods Schweizerische Kephiranstalt.

- Wehsarg, R. (1928). Moderne Milchtherapie bei Verdauungsstörungen und Tuberkulose. Verlag der Aerztlichen Rundschau Otto Gmelin.