Take home message

- Traditionally, raw milk was matured/stored in a wooden vessel before making the cheese. The bacterial biofilm present on the wooden surface is a main source of lactic acid bacteria, which in their diversity ensure the flavour of the final cheese.

- Hygienic milking and a wooden cheese vat prevent, that unwanted, zoonotic bacteria can develop into the cheese milk.

No stainless steel

Today, everything around milk and milk processing is stainless steel (INOX). The cheese vat in which the milk is processed is stainless steel, the milk pipelines through which the milk is pumped and even parts of the milk claw are stainless steel. Of course, this has been different in early times, and traditionally, farmhouse cheese was made in wooden, single-walled vats. This is still done sporadically today. Among others, a sheep’s milk cheese from Sicily, but also cheese made in a monastery is still made in a wooden vat. The peculiarity of the cheese is that no lactic acid bacteria (as a starter culture) were added, and there is only a spontaneous acidification. The milk is milked by hand, strained and stored overnight. It is stored in a wooden vat. The next morning, the warm morning milk is added, and the milk is curdled with rennet. This process overnight is called ‘milk ripening’, which allows bacteria in the raw milk to develop and grow to a limited extent.

Where do the bacteria and yeasts come from,

…. and how do they multiply in the milk and final cheese, and how dangerous is such a cheese in terms of hygiene and zoonoses? By Dennis D’Amico’s microbiology lab (Connecticut, US), nearly 120 samples were collected from hands, walls, cheese milk, cow teats, barn air, spots in the wooden cheese vat, and cheese storage in a nunnery’s cheese factory (https://abbeyofreginalaudis.org). Different stages of milk (extraction, filtering, storage, maturation) and the cheese were tsampled (Sun and D’Amico, 2021).

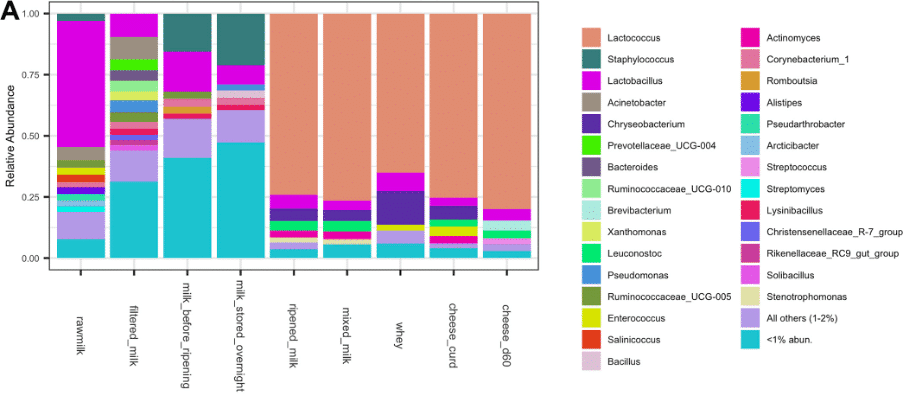

More than 44 bacteria and 29 fungi were found on walls, hands, wooden utensils, etc after DNA analysis. Based on the similarities and differences in the cheese milk, one could make a clear dichotomy in the milk samples: (1) the raw milk immediately after milking, milk that had passed through a filter (sieve or teems), milk kept overnight and the milk before ripening, and (2) the ripened milk together with all samples taken afterwards uptil the cheese itself.

Bacteriologically, you can see a clear boundary before and after milk ripening (bars 1-4 and bars 5-9 in Fig. 1, respectively). The orange bar in the last five samples is Lactococcus. After maturation in the wooden vat, Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus spp., and Leuconostoc spp. species found on the wooden surface of the cheese vat dominate. Within 12 hours of contact with the wooden tub, the diversity of bacteria found in raw milk is virtually gone, reduced to the quantitative predominance of a few bacterial species. The favourable ripening temperature is a huge incentive for the mesophyll lactic acid-forming bacteria to grow out. There is a similar figure for the fungi the yeasts, where eventually mainly Kluyveromyces and Exophiala fungi dominate after ripening (not shown).

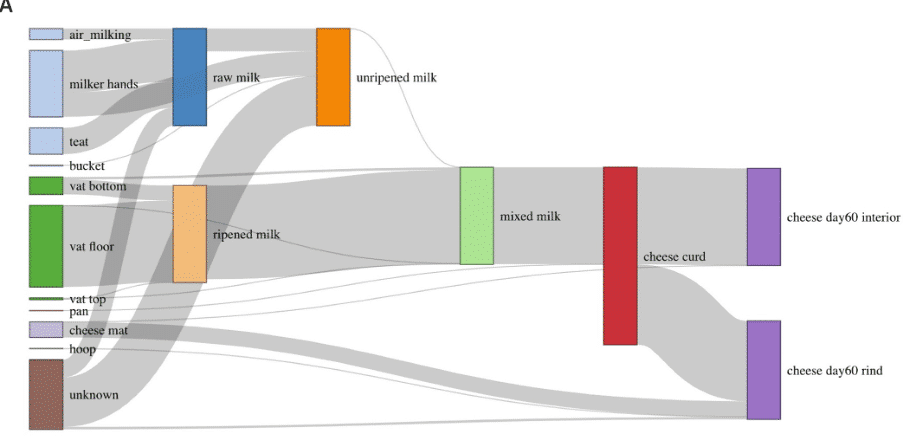

The authors then depict in a flow chart, where bacteria find their origin and how they are found in the different steps from milk to cheese (Fig. 2). Using the thickness of the grey line, you can follow up beautifully, how this proceeds. For the raw milk (dark blue), the main source is the milker’s hands (43%), followed by the cow’s teats (27%) and barn air (11%). In the unripened milk (orange), in addition to the similarities with the raw milk, unknown sources (brown) are originally fed. The matured milk (light orange) corresponds to that found in the wooden vat, together 99.7% (dark green). The most striking thing is that when warm morning milk is mixed with matured evening milk from the evening before, in the mixed milk (light green) the bacterial influx from the unripened milk almost disappears; there is only a very thin grey line from orange to light green. In the curd (red), there is no distinction from the bacterial composition of the mixed milk. The same applies to the 60-day-old cheese (lilac). Only the rind (lilac below) still has an input from the cheese shelves or mats on which the cheese matures. The flow diagram of the moulds and yeasts does not look substantially different (not shown).

Dangerous, unwanted bacteria?

The entire chain was tested for the presence of unwanted zoonotic bacteria (such as Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridium botulinum, Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella spp., pathogenic Escherichia coli, coagulase-positive Staphylococcus, and Bacillus cereus). None of the bacteria were found anywhere. This is remarkable, since the modern view on hygiene in cheese-making is based on smooth surfaces of stainless steel, which are easy to clean. The authors give two explanations for this absence, namely the low germ count of the starting milk and the use of the wooden cheese vat. Such cheesemakers know, how to milk and clean hygienically, and thus achieve a germ count of below 1,000 germs/ml (3 log10), which is also the experience of German Vorzugsmilch (Berge and Baars, 2020) and of the Raw Milk Company, where kefir is made twice a day from fresh, warm raw milk. Studies further show that the biofilm that develops on wood protects against the growth of unwanted bacteria. Sun & D’Amico (2021) call this the ‘bio-protection via the secretion of anti-microbial substances’, so there is strong competition for raw materials, like lactose, by the lactic acid bacteria in this biofilm.

Terroir

Thinking about the concept of terroir, as promoted by the French, it stands for two things: the uniqueness of the local product and the balance of the microbial world, where no harmful bacteria can develop. Apparently, this traditional method of preparation encompasses all the characteristics of a terroir, with the ecosystem of lactic acid bacteria that have established themselves in the wooden vat wall. These not only determine the smell and taste of the final product, but also regulate, that no zoonotic bacteria can grow into the cheese. They are suppressed by the diverse lactic acid bacteria population.

Literatuur

- Sun, L., & D’Amico, D. J. (2021). Composition, Succession, and Source Tracking of Microbial Communities throughout the Traditional Production of a Farmstead Cheese. Msystems, 6(5), e00830-21.