Lactose intolerance

Lactose is milk sugar, found in a concentration of 4-5% in cow milk. People with lactose intolerance cannot digest lactose in the small intestine, so too much undigested lactose ends up in the large intestine. Here, lactose causes problems because the colon bacteria release unwanted gases such as methane and hydrogen from the lactose. Result: bloating, flatulence and pain in the lower abdomen. Most western people have undergone mutations that allow the enzyme lactase to remain active once breastfeeding has stopped. This is unique to our genetic adaptation to dairy consumption. The enzyme lactase remains active and converts lactose into galactose and glucose, sugars that can be further split. Cheese country Switzerland has a large research institution in Bern, the Forschungsanstalt für Milchforschung, now part of the umbrella Agroscope. In 2019, research was conducted on the lactose concentration of 121 different dairy products eaten in Switzerland (Walther et al., 2019). The researchers also analysed the breakdown products galactose and glucose, and a good picture emerges, how lactose concentration decreases from the unfermented products like milk, cream and butter, through the yoghurt and cottage cheese, the fresh cheeses to the aged cheeses. As a control, lactose-free milk and cheese varieties were analysed.

Cheese, dairy and lactose

Both when making (semi-)hard cheese or fresh, sour dairy products, lactose is converted into lactic acid. Lactobacilli convert milk sugar (lactose) into lactic acid. However, the bacteria themselves stop this breakdown process by being unable to grow at lower pH levels. The pH is then just over 4.0. Not all the lactose has disappeared. In yoghurt, for example, about 2/3 of the milk sugar is still retained. It’s different in cheese (soft cheese, semi-hard cheese and aged cheese), which is left to mature for shorter or longer periods of time. Over time and after longer ripening, the lactose is almost completely broken down and no lactose can be found (below the laboratory detection limit). In other words, these products can be considered lactose-free.

Lactose-intolerance and dairy

Despite the still high levels of lactose in sour dairy products like yoghurt, yoghurt is not known as a ‘problematic product’ for lactose-intolerant people. This is probably, because people eat dairy, which still contains live bacteria and enzymes. Walther et al (2019) write: ‘bacterial lactase activity persists in the digestive tract. Thanks to the pH buffering capacity of yoghurt and its longer residence time in the stomach, 90 per cent of the lactose in yoghurt is digested before it reaches the small intestine. The residual amounts of lactose that reach the colon are so small that the symptoms of lactose intolerance hardly occur’. In other words, yoghurt sends its own enzyme system along in the stomach and intestine, leading to the huge residual lactose reduction anyway. In addition, the researchers indicate, a product does not have to be completely lactose-free, even for the truly lactose-intolerant: ‘Several experiments show, that most people with lactose intolerance can normally still consume 6 to 12 g of lactose per day without symptoms. This means that consuming 1 dl of milk and a bowl of yoghurt need not be a problem for them.’ The latter might explain the huge increase in dairy consumption in a country like China, which is fully populated with lactose-intolerant people. Chinese people still can consume dairy in (very) limited amounts, including a glass of milk. Earlier, we wrote about the cultural adaptation of pastoral peoples who live from their milk on the steppes of Mongolia. These Asian people are genetically completely lactose-intolerant, but they have their fresh drinking dairy acidified to the point where virtually all lactose is gone. The consumption of only sour dairy as a cultural solution to lactose intolerance.

Lactose reduction

So, the absolute amount of lactose in dairy does not tell all about the possibility of digestion by lactose-intolerant people and the gas formation problems and pain in the intestines.

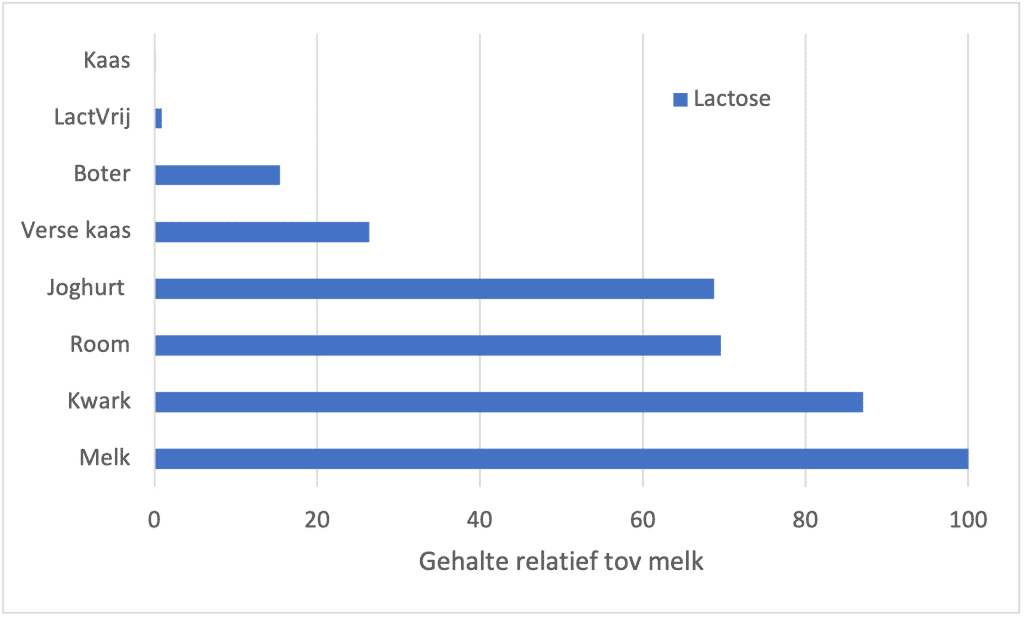

Figure 1 shows 121 products from Switzerland divided into different dairy groups. In the graph, the products are compared to milk, full, or skimmed. Milk contains almost 49 grams of lactose per kg. All other products contain less lactose. The lactose content in milk is set at 100% and compared with the lactose content in the different dairy groups.

Differences in lactose in dairy arise from three things: fermentation; thickening/concentration and ripening. Milk and cream have a lot of lactose because they are not fermented. Milk has more lactose than cream because cream is made up of fat and has less skim milk which contains most of the lactose. When you acidify milk (the yoghurt group), the lactose content in the product decreases by about 1/3. This is due to the conversions into lactic acid, mentioned above. It does not acidify further, because the Lactobacilli ‘poison’ their own environment, so to speak. If you start thickening a soured product into cottage cheese, the lactose content in the product increases again slightly, because there is a further increase in lactose concentration.

If you look at cheeses, fresh cheeses (here: Hüttenkäse and Mozzarella) still contain lactose. However, when cheese has undergone some ripening, all further lactose is converted during ripening, and the lactose-free products emerge.

Finally, the enzyme lactase is added to lactose-free products, which means that these products have very low concentrations of lactose. Despite the word ‘lactose-free’, all these products contain small residues of lactose, while the cheeses mentioned all fall below the lab’s detection limit.

Galactose appears

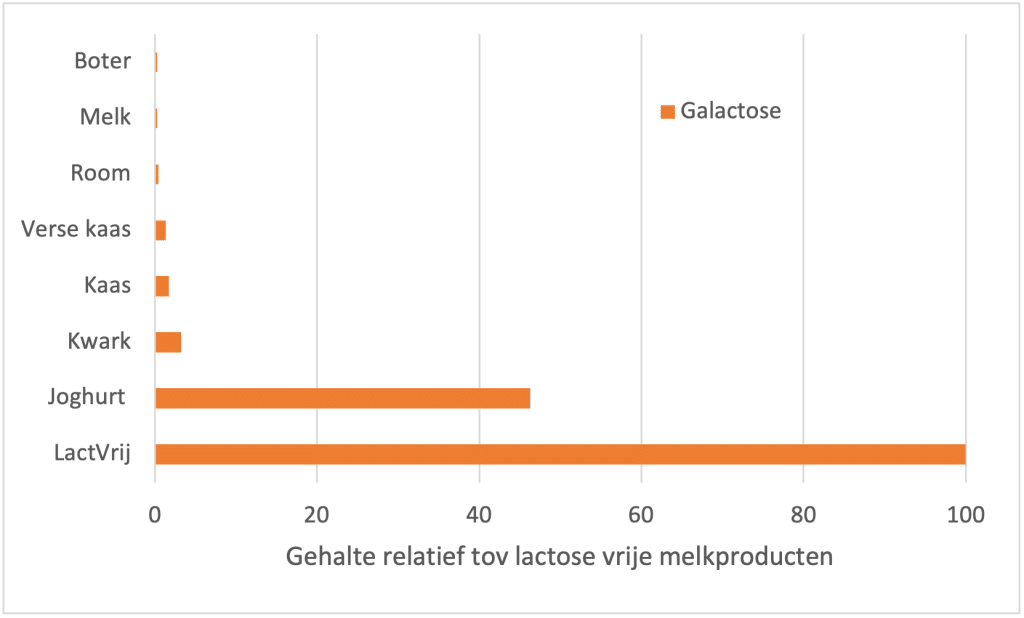

From lactose (C12), both glucose (C6) and galactose (C6) are formed. In further degradation, lactic acid (C3) is formed.

You will find maximum galactose in lactose-free products because the added enzyme lactase splits all the lactose into galactose (18 g/kg) and glucose (17 g/kg). Milk, butter and cream are not fermented and therefore have no galactose formation. In yoghurt, part of the lactose is converted (1/3) by the Lactobacilli and, in the process, mainly galactose accumulates. In the second step of transformation, glucose in yoghurt is consumed first and converted to lactic acid. In cheese and fresh cheese, hardly any galactose is found, slightly more is found in cottage cheese.

Conclusion

Lactose intolerance does imply, that you cannot eat dairy products. Due to the breakdown of lactose into lactic acid and further ripening in cheese, lactose will no longer be found in cheeses, except for fresh cheese (Mozzarella, Hüttenkäse). Besides artificially lactose-free products, most cheeses are a good alternative for lactose-intolerant people.

High levels of lactose are still found in fresh dairy products such as yoghurt and cottage cheese. Due to the slow digestion in our gastrointestinal tract plus the presence of active enzymes in the dairy product, which convert the residual lactose, only 10% of the lactose in yoghurt reaches the colon. This small amount of lactose does not usually cause a problem, even in lactose-intolerant people. All in all, therefore, it is not only the lactose content that determines whether a problem with lactose digestion arises.

Literature

- Gille, D., Walther, B., Badertscher, R., Bosshart, A., Brügger, C., Brühlhart, M., … & Egger, L. (2018). Detection of lactose in products with low lactose content. International Dairy Journal, 83, 17-19.

- Walther, B., Gille, D., & Egger, L. (2019). Konsum von Milchprodukten trotz Laktoseintoleranz und Galaktosämie. Schweizer Zeitschrift für Ernährungsmedizin (SZE), 17(4), 24-27.