Take home message

- Cheese making in a natural way exists, with its own mesophilic starters and homemade rennet. From soft cheeses to the hard cheeses.

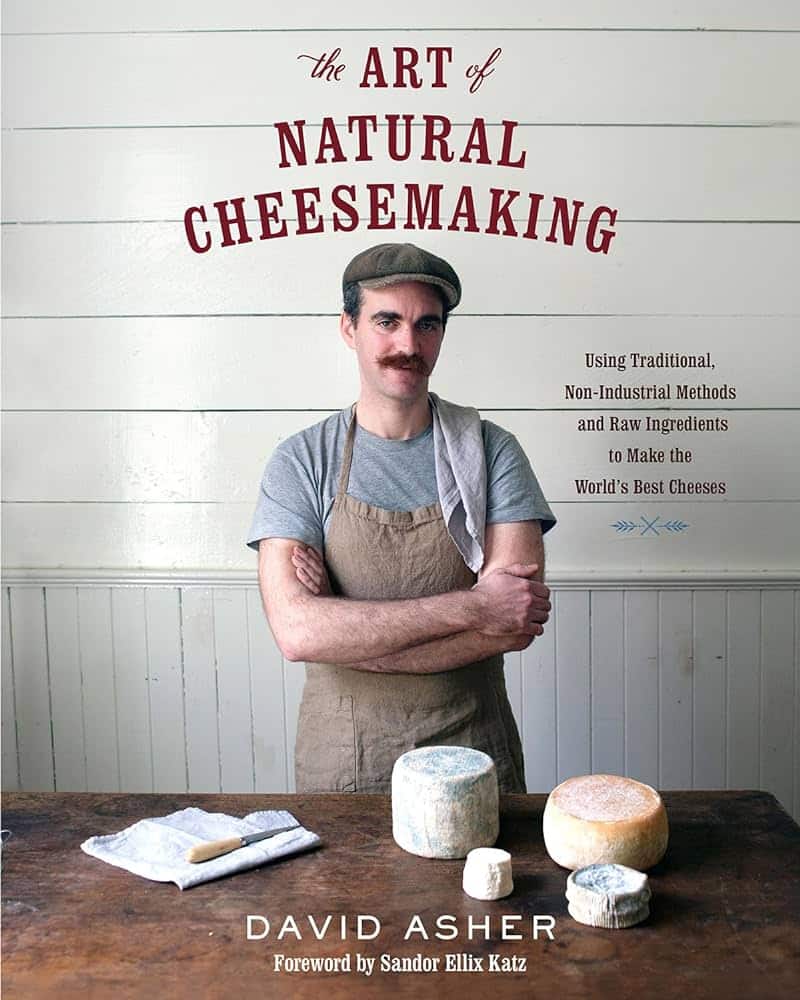

- David Asher is an advocate of this principle. Years ago, he decided to make this his life’s work, with success.

5-day training course

During the last week of May 2024, he taught a 5-day course at a Bio-Suisse farm in the Jura. In a tight program, one or two types of cheese were made daily. In addition, the 20 participants were informed about starter cultures, making their own rennet, the importance of warm milk, the digestion process of milk in the baby’s stomach, storing cheese, why fermentation and many other things. There was tasting, stirring, making, demonstrating. Especially the ease with which David handles hygiene was a great eye-opener, in addition he was able to provide lots of observations, how to gain confidence in the process, the outcome, the pH and the ripening of cheese. Asher offers insight into the process of fermenting milk, which has guided us for centuries. His view strongly supports the work of Weston A. Price, who showed, how fermentation was used everywhere in all cultures around the world to preserve food, and how fermentation contributes to the health of naturally living people.

Families of dairy products

In five consecutive days, David Asher walked through the world of dairy products: (1) fermented milk; (2) fresh cheese; (3) white mold cheeses with rennet; (4) blue cheeses with rennet; and (5) semi-hard and hard cheese based on rennet and heating the curds. Depending on whether the starter dominates, or the rennet has its effect first, you get a different type of dairy. Furthermore, you can derive cheeses by further processing. Cheddar, for example, is prepared by destroying the fresh curd and re-pressing a type of Gouda cheese. This gives you a long-lasting hard cheese. Mozzarella as part of the pasta filata cheeses is made by heating your fresh curd, making it gummy and allowing it to be kneaded into a cheese ball. David’s philosophy is, that you can make basically any cheese from milk by adjusting end temperatures, curd size, use of rennet, resting and stirring times, and ripening (time, bacteria and/or mold) and rind treatment (redsmear, white mold). Some cheeses require blue mold. A thermophilic starter culture is additionally used for yogurt and mountain cheese or hard cheese. All other dairy products are made with a mesophilic culture. Such cultures impart more flavor because the bacteria can produce numerous flavorings plus alcohol. Although similar cheese types are made in very different regions, the principle of each cheese type is understandable, if you know how to play with the above factors.

Kuhwarme Milch

Funnily enough, certain terms are not well expressed in all languages. Milk, which is still cow warm, means milk that is less than an hour old, is fresh. This is different from warmed milk, which you never know if this milk has not already been kept cold (refrigerated) for 12 or 24 hours before being reheated (on the stove) to body temperature. In English and French, they don’t have words for this.

Kuh-warm milk is part of the 2x daily cheese making process. The warm morning milk or warm evening milk is processed into a dairy product, ‘Kuh-warm’ (in German), immediately after milking. Here is a big secret to the success of traditional, natural cheese making. It hardly takes place anywhere anymore, as everyone has switched to cheese made from at least 2 or even 3-4 milkings. Not to mention robotic milking, where milk is ‘collected’ throughout the day and kept refrigerated before cheese making can begin. Body warm milk is that which is transferred from the breast plus nipple or the udder plus teat from the mother to her child. Always fresh and at the right temperature (body temperature), the milk enters the stomach, where enzymes and an acidic environment ensure, that the milk flocculates (becomes thick) and that the enzymes first target the casein (cheese substance) and break it down into peptides and amino acids.

Cheese whey

A beautiful word for cheese whey in French is ‘le petit lait’ (the little milk or the small milk). Cheese whey is created in large quantities during cheese making. Livestock farmers have sought numerous ways to use, or further process, the acidified cheese whey. Evaporation takes an enormous amount of energy and distorts the whey proteins. Whey is popular among athletes today; it contains numerous proteins that aid in muscle repair and building. Eventually, much of the whey ends up in the animals; calves, pigs and even cows were supplied with cheese whey. In the course, each day there were trays of sour whey. Asher demonstrated, how you had to ‘wash’ your hands and arms in the whey before you touched the cheese milk, the curds, with your hands. A different attitude and relationship to hygiene emerged. Cheese whey as a detergent, as a skin care product are also among the possibilities.

Wooden cheese vat

In the Netherlands, in the peat meadow area, Gouda cheese was made on the front part of the tied barn. The cows all went out in the spring and stayed outside until the end of the summer. The barn was freshly limed, and the cheese vat put down. Traditional cheese vats were often made of chestnut wood, which is lighter in weight as the teak (tropical) or oak. Now cheese is still made in wooden vats in some areas of Italy and France. Once in use (2x daily), there was no need to use a starter culture. The lactic acid bacteria appeared from the cracks in the wood. Because of our increased hygiene, closed milking systems, cleaning of teats and milking machines and especially the stainless-steel cheese vats, which are scrubbed and disinfected daily, it is necessary to add homemade lactic acid starters to the cheese milk. We have made the cheese milk itself ‘too sterile’, or too poor in germs, and it lacks chinks in wooden walls, which prevents spontaneous acidification of the cheese milk, from taking place.

Starter cultures

Allowing cow-warm, raw milk to spontaneously acidify and inoculating it daily into fresh, raw milk produces a starter culture. It may take a few days, and several inoculations to get the lactic acid bacteria you need to prevail. These are mesophilic cultures, bacteria that grow well at 20-25o C. If you do this consistently daily, you’ll have an active starter culture on hand every 12-24 hours, doing its work immediately in the warm milk. A starter culture, which you want to store, should be put away refrigerated; then the bacteria will stay alive, for several days. Lactic acid bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, but die, if you don’t feed every 24 hours with fresh, cow warm milk.

The principle you use to make your own starter is called back-slopping. That is, you add a small amount (2-5%) of active, living and growing starter culture to a new amount of milk. You basically do this, too, when you make raw milk kefir from grains; you use the grains as the starter culture for your new kefir, and the kefir itself can be used as the starter culture in the cheese vat. For kefir, using it within 24 hours primarily produces a starter culture containing lactic acid bacteria. If you leave it for an additional 12 hours, the yeasts will also develop. This is because the yeasts live off the lactic acid, which has just been made by the bacteria. The similarity between the wall of a wooden vat and kefir grains is that they both house your starter culture, your lactic acid bacteria, which are necessary in any dairy product.

Rennet

Once your starter is present, only rennet is left to make cheese. Depending on the type of cheese, none, a drop or a good amount of rennet is used. Rennet was originally made in-house from the abomasums of nearly sober calves slaughtered within 1 month of birth. In the Netherlands, the rennet came from the Leeuwarder rennet factory; each country had its own rennet makers. By now, rennet production for all of Europe was in the hands of the largest supplier of freeze-dried starters. The origin of this commercial rennet is calves from New Zealand, where it is still the custom to kill most of the calves immediately after birth. Some independent suppliers of rennet can still be found, especially in Spain and often goat lambs as a basis.

Rennet-ethics

David Asher made a clear plea that with the use of cow’s milk, goat’s milk and sheep’s milk for cheese production, an agricultural culture has been created, in which we humans decide the fate of our animals. With eating cheese also comes the realization, that you must sacrifice young animals to use their abomasums. For 1000s of years it was the custom to kill a significant portion of the newborn animals. There was just not enough grass and fodder to raise all the animals and give them a life. Few male animals (bull, buck) were needed to get the females pregnant; 1 bull in 10-50 cows was more than enough. One also needed only a proportion of females to replace aging cows and goats (less than 30%). For good reason November was the month of slaughter. All animals that one could not feed through the winter were slaughtered, their meat processed, pickled or dried.

The livestock farmer realized early on that he/she had to kill in order to feed himself/herself and his/her fellow humans with valuable foodstuffs such as butter, cheese and dairy. Today, we want all calves to have a dignified life. Asher calls this the “bambification” in animal husbandry caused by the Disney movies in the 1960s. There was a resistance to the killing of young animals, of animals in general, and there came the ethical question of dignified life. A dignified calf life means a life in calf fattening farms, long transport routes across Europe and a concentration of animals on the North Veluwe, for example. Killed they are anyway, however now with iron deficiency (white veal), with many animals together, under the protection of an antibiotic blanket on stalls with slatted floors.

Demonstration and simplicity

What is striking is with how much calm and overview, insight into the dairy is demonstrated. David Asher teaches you to look, smell, feel, taste, so above all, trust your senses. Phenomenology pure and simple. There was patting the top of the curdled milk with the hand, looking at the first traces plus later ridges of Geotricum growth with backlight, looking at the flocculation of the milk to assess pH (flocculation; pH = 4.5; stretching curd: pH = 5.3), there were simple measures of curd size (lentil, hazelnut, walnut), there were simple tests to judge curd maturity (Matterhorn test, splash test, spaghetti test, bouncing test), there were simple ways to grow Penicillium, a blue mold (keep old good sourdough bread moist). There was also thorough information on the backgrounds of sourdough (meso- and thermophilic), rennet, the inner curd of each cheese, molds and yeasts, and above all, lots of demonstrations.

For David Asher, cheese making is still a form of alchemy. Rather, what today’s industry has made of it is a form of chemistry. Asher wants none of that and shows that the alpha and omega of natural cheesemaking is the ‘fresh, cow-warm milk’. Along with the love of the process.

Courses

Asher regularly teaches 5-day courses throughout Europe. His views on cheese, his courses can be found under https://www.milklab.ca/