Take-home message

- Genetically lactose-intolerant healthy adults consume less lactose and dairy than lactose-tolerant adults. However, the intestines of lactose-intolerant individuals who consume larger amounts of lactose harbour more lactic acid bacteria and acetate-producing bacteria.

- Besides genetic adaptation and cultural adaptation, this seems to be a 3rd way to consume lactose, especially if you are genetically unable to digest milk and dairy. Let the bacteria do the work.

Lactose intolerance is not lactase non-persistence

Complicated word choices due to double negations. The issue is whether and how you can (still) digest lactose from milk products, especially milk, later in life.

Lactose tolerance is usually seen as a genetic characteristic of the (predominantly) western European-derived white population, Caucasian humans. After 10,000 years of society with sheep, goat and cow and the consumption of their milk products, there are mutations in our DNA that prevent the ‘lactase’ gene from being turned off, when the flow of breast milk ceases. Indeed, we continue to consume milk, mostly from the goat or cow. All milk contains milk sugar, or lactose. This energy source is split by the enzyme lactase into glucose and galactose, and these sugars are further digested into carbon dioxide or also lactic acid (lactate), among others. Lactase persistence is thus the term, indicating the “staying on” of the enzyme lactase after breastfeeding, a genetic adaptation. The adaptation is attributed to centuries of using dairy products, like cheese and characterises humans who have settled down and started farming and animal husbandry. (Other) genetic adaptations to be able to digest sweet milk are also found in African peoples, just like in Caucasian humans. Globally, it is estimated that about 68% of the world’s population cannot digest lactose as adults. For Asian people, almost 100% cannot digest lactose.

There appeared to be a 2nd way to still continue consuming milk products as adults, namely through a cultural adaptation where the milk is fermented (before consumption) with bacteria. Drinkable milk products from herders in Tibet are (very) acidic and low pH (<4.0), so the milk is pre-fermented outside our bodies, so to speak. The cultural adaptation is found in these pastoral peoples, who are genetically completely lactose intolerant; that is, they have not become genetically adapted like Western or African pastoralists. Such dairy products are also known to us. Matured cheese, yogurt or kefir, for example, contain (much) less lactose than the milk from which they are made. Both ripening (age of cheese) and the pH (acidity) of the milk product determine how much residual lactose a milk product still contains.

The 3rd way via gut flora adaptation

In a proportion of genetically lactose-intolerant people, researchers have found evidence that their gut flora is different (Kable et al., 2023). Instead of producing an enzyme lactase, these people cultivate certain groups of bacteria in their gut, which do the fermentation work for them. Not unlike cultural adaptation like the Tibetan herders, who organised fermentation prior to consumption, this is an incorporated solution, a solution in your own body, the gut that is. It’s not a genetic adaptation, but it’s still an adaptation that you can rather refer to as epigenetic.

In healthy adults in the US, consumption of dairy products was looked at in combination with the presence or absence of a particular gene for lactase persistence (LP gene or rs4988235 genotype). Dairy patterns were assessed via fill-in forms, from which the amount of lactose people ate was deduced. Furthermore, a poop sample was examined for its gut microbial composition.

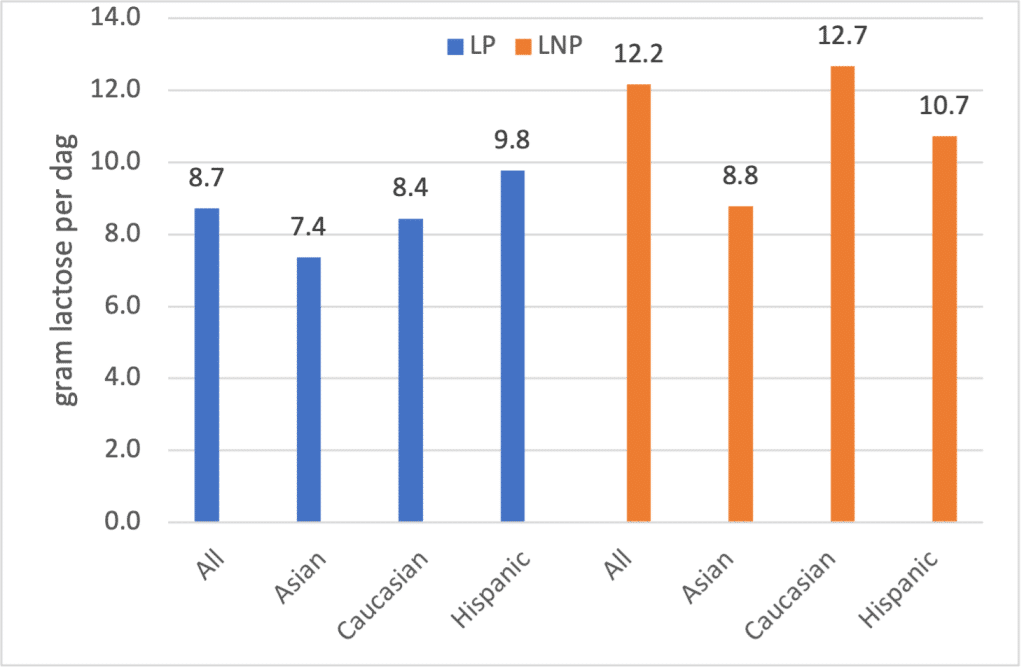

Analysis of food-frequency forms showed that people in possession of the LP gene ate more lactose than non-LP carriers. This makes sense, they can convert lactose without unwanted gas and abdominal pain via the lactase enzyme they have created themselves. It applied to men, not significantly to women and especially within the Caucasian population. Differences in calculated lactose consumption was also higher in Hispanics and Asians (see figure), but there were mixed groups where this was not true (not shown). Across the whole sample (n=279), LP carriers consume 12.2 g of lactose per day compared to 8.7 g in the non-LP carriers. Their dairy consumption is also higher.

Fig. 1. Differences in lactose consumption (g/day) within three population groups (Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian) and the whole group of 279 people, split by adult with and without genetic ability to digest lactose. LP = Lactase persistent; NLP = not LP. (Data from Kable et al., 2023)

The NLP group, thus genetically unable to digest lactose, was divided into four classes of lactose intake (low, medium, high, very high). It was then looked at, how the gut bacteria differed between the groups. What emerged was that the Lactobacillaceae family, the lactic acid bacteria were higher in the group with the highest lactose consumption. Less strongly, the same was true for the family Lachnospiraceae.

Many lactic acid bacteria produce the enzyme β-galactosidase, which splits lactose into glucose and galactose. The family includes the genera Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus and Enterococcus. Other studies have also already shown, for example, that Bifidobacteria are higher in the gut of NLP than LP, which may explain that despite the different genetics (unable to digest lactose), certain groups of gut bacteria take on part of that role and are present in higher concentration in the gut.

In short, there is a role for gut bacteria to digest milk products, especially in those who are genetically unable to digest lactose.

Literature

- Kable, M. E., Chin, E. L., Huang, L., Stephensen, C. B., & Lemay, D. G. (2023). Association of Estimated Daily Lactose Consumption, Lactase Persistence Genotype (rs4988235), and Gut Microbiota in Healthy US Adults. The Journal of Nutrition.